Here’s a brief cross-post about editing devices from the Complete Works of Edith Wharton editors’ site.

Volume Editors have many methods of comparing texts, some of which are text based (relying on typed text) and some of which are image based (relying on photographs or physical volumes). If you have other resources, please feel free to add them here. See also the works in the bibliography for the Editorial Guidelines and the brief guide to editions, printings, and states here: https://www.abaa.org/blog/post/first-state-notes

Different methods, text-based or image-based, will work better depending on what you’re comparing.

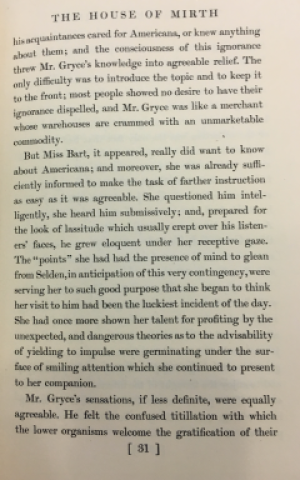

- EDITIONS, which will usually be set from different plates and have different typefaces and page numbers (e.g., Scribner’s first edition, Macmillan [British] first edition, and so on), can’t be compared with image-based technology because of the the differences in typefaces and pagination. What’s on page 31 of the Scribner’s first edition of The House of Mirth will not be similar enough to what’s on page 31 of the Macmillan edition to make a comparison of individual words and letters possible, for the words will not be on the same lines. EDITIONS will need to be typed so that the text can be compared using Juxta or another text-based method.

2. PRINTINGS, which will be printed from the same plate as the first edition with the same typeface and page numbers, will differ little in appearance. The same material will be found on p. 3 of the Scribner’s edition, first printing and the Scribner’s edition, 5th printing, and the words will appear on the same line. PRINTINGS can be compared using image-based comparison methods like the Hinman or other image-based technologies.

The image on the left is from page 31 of the first Scribner’s edition of The House of Mirth; the second image is from page 31 of the Macmillan (British) first edition.

Text-based comparisons

Text-based comparisons let you look at the differences between two typed documents. Most of us are already used to doing this in Word, but Juxta Commons is useful for more complex comparisons.

Text-based methods are useful when you are comparing different EDITIONS of a book.

Juxta Commons. http://juxtacommons.org/ This easy-to-use and free software can compare two screens of text at once and can identify the differences by highlighting them. Juxta looks like this:

To get typed text to compare, you might try these:

-

- Typing the volume into a text editor (like Notepad or Text Wrangler) or into Word.

- Using a typed version or the raw OCR (Optical Character Recognition) version found online that you proofread carefully against the copy-text volume (usually the first American edition). When raw OCR text comes out of the scanner, you’ll see that it is kind of a mess. There are odd characters, like ! instead of 1, m instead of rr, and even worse. You can see a little of this if you try to convert a .pdf document back into text using Google Docs. Whenever scanned text is used, it has to be carefully proofread.You may see references to “cleaning” the raw OCR text. “Cleaning” is just a term from data processing; it means to correct the data (in this case the text) according to the scanned material so that it makes sense.

- Adobe Acrobat Pro can turn .pdf files into text, but the text it creates must be carefully proofread.

- Google Docs is supposed to be able to turn .pdf files into text, but the text it creates must be carefully proofread.

- Scanning the copy-text volume with a specialty software such as ABBYY Finereader https://www.abbyy.com/en-us/finereader/ This text must also be carefully proofread but is supposed to have fewer errors than other scanning to OCR (Optical Character Recognition) kinds of programs.

Image-based comparisons

If you have taken pictures of several printings of the volume you’ll be editing, image-based or digital comparison software will be helpful.

- Traherne Digital Collator, a free comparison and collation software. The Traherne Digital Collator compares two page images so that you can see differences between, say, the first and second printing of a volume.

The download links can be found here: https://oxfordtraherne.org/traherne-digital-collator/ and http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/software/traherne/. These methods work for different printings or states of the same edition but not for different editions that have different fonts.

In the screenshots below, the top image compares the first edition of The House of Mirth, from a copy in the Lilly Library, with a copy of the first edition in the Beinecke Library. Note the broken character on the running title (HOUSE), which is illuminated by a red color instead of purple in the second image.

2. Pocket Hinman. The Pocket Hinman is a free experimental app developed for James Ascher and DeVan Ard. It’s available for iPhone and Android through the App store and here: https://rossharding.me/#/pockethinman/

The Pocket Hinman allows you to compare visually a volume that you’re looking at with a previous picture of a volume. Differences will stand out by flickering slightly.

Mechanical Comparators and Collators

If you live near a research library or are visiting one, you can use these older devices to compare physical volumes of the text: the two major kinds are the Hinman Collator and the Lindstrand Comparator.

Hinman Collator. Developed by Charlton Hinman from WWII bomb target technologies that compared two images and found slight differences by flickering images and used in creating comparative versions of the First Folio, the Hinman Collator can find small differences that indicate changes from one printing to the next.

Here’s article from the Folger Library that describes the Hinman in more detail:

https://collation.folger.edu/2018/05/hinman-redux/

Here’s a demonstration of the Hinman Collator in action, with text by James P. Ascher, who developed the Pocket Hinman:

The following article from 2002 that gives all the then-locations of Hinman Collators, Lindstrand Comparators, and other mechanical editing devices. Each of the major Edith Wharton archives has a Hinman or Lindstrand machine available.

“Armadillos of Invention”: A Census of Mechanical Collators

Author(s): Steven Escar Smith Source: Studies in Bibliography, Vol. 55 (2002), pp. 133-170 Published by: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40372237